A Eulogy for Simon's Rock

My undergraduate institution is, effectively, shutting down. I am grieving as I would an old friend.

This Tuesday, November 17, 2024, at 1:00 PM, the faculty of Bard College at Simon’s Rock were told that the school is being consolidated with Bard’s main campus, and that the Simon’s Rock campus will close at the end of the term. Forty-five minutes later, the student body were told.

Sometime in that 45 minute span, my world ended.

I’m still grieving, still processing. This news came when I was grieving Simon’s Rock anyway as a very recent graduate; my first quarter of graduate school has me questioning how much of my love for academic work was actually love for how Simon’s Rock in particular operates. I can’t blame John Weinstein, our provost and a personal mentor of mine; I do believe him when he says that this option was the only one available under the financial and bureaucratic circumstances that could preserve some semblance of the school’s mission and philosophy.

I don’t quite know how to explain what this place meant to me. Plenty of others—current students, fellow alumni, even faculty—have said the words “Simon’s Rock saved my life,” but they ring hollow without tangible specifics. I don’t want to continue to give my admissions representative spiel when they’re not paying me to do so. I don’t want to act like this institution is an uncomplicated good—it was recently brought to my attention that it has, at the moment, one of the most expensive tuition rates in the country, with not much glamour in its campus life to show for it. It was also the first home I loved, and the first home I understood to love me back.

In 2020, I was sixteen years old and, much like the rest of the world, depressed and deeply scared. I had completed my first two years of high school with a bruised and bloodied sense of self. I held certain truths dear: that I loved to learn, because learning is all there is; that my experience of high school was crushing my soul and had very little to do with learning; that I was a person and the systems I existed under did not see me as such.

So I left.

On August 23, 2020, I (masked and alone, with my mother socially distanced in the car) moved into a college dorm on a campus I had never visited (my post-acceptance tour had been scheduled for April 17, 2020) along with roughly ninety other fourteen- to seventeen-year-old students. We spent ten days in complete in-room isolation, many of us with roommates we had never met before.

After those ten days, it was as if the world had opened up to me.

I was sixteen years old, and professors not only wanted to hear what I had to say, but expected it. I was sixteen years old, and all adults in my community went by their first names; their qualifications did not mean their personhood was worth more than mine. I was sixteen years old, and I was assigned writing and thinking that I cared deeply about and wanted to complete well. I was sixteen years old, and for the first time in my life, I was surrounded by peers who wanted to be at a school.

My autistic special interests, which previously had been at best a hindrance to my academic progress, were my best asset as a Simon’s Rock freshman. In my first month of classes, I developed a fixation on British steampunk concept band The Mechanisms and their musical adaptations of mythology and classic literature; in my second month of classes, my academic advisor, Asma Abbas, told me about her current passion project. The next semester, she invited me to register for the Transdisciplinary Studio, a four-credit shared workspace for students to incorporate critical thought into personal passion projects. Over the next three years, I wrote, casted, and began to record a science fiction audio drama adaptation of Hamlet, encouraged and supported by both Asma and literature professor Jane Wanninger.

Any idea or interest I had, no matter how silly or “un-academic” it seemed to me, was met with joy and curiosity by faculty, and was incorporated into my studies however possible. The personal and the academic did not have strictly defined boundaries, nor did academic disciplines from each other. When I got COVID-19 at the end of my sophomore year, Jane and I talked about my summer plans through the closed window of my quarantine housing, and she left a succulent at the door to keep me company through the rest of my illness.

I attended Simon’s Rock for four years, an experience most of its recent students do not share; my BA class of 2024 had a total of twenty graduates compared to this year’s seventy-something AA graduates. Most students transfer after two years upon completion of their AA; along with the campus, it is specifically the Simon’s Rock BA program that is being eliminated by this change. Simon’s Rock AA graduates will now automatically matriculate into Bard proper, which I find to be a truly heartbreaking loss.

When my classmates made their mass exodus from campus between sophomore and junior year, I found the studies and friendships that truly shaped me. The size and structure of Simon’s Rock allow for uniquely transdisciplinary and self-directed work, especially in the upper college. My cohort of graduates were a close-knit community both socially and intellectually; my work as a media studies and education scholar was strongly informed by the work of my partner, who was a dual major in creative writing and biology, as well as our friends in psychology, theatre, and visual art. I was given the tools to explore topics not covered by any predefined course through Asma’s Studio, tutorial classes, and personal support from professors.

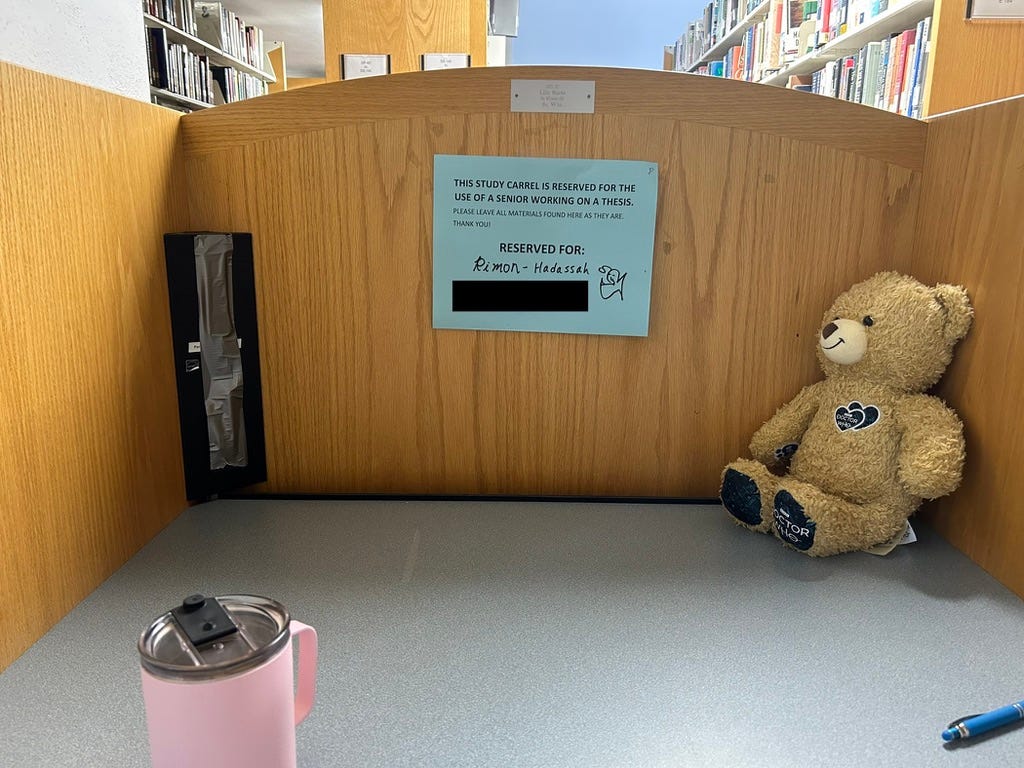

Working on my senior thesis was the most gratifying and fulfilling project I’ve ever done. Sometime early in my junior year I had already decided on a topic: I was going to write about the fandom of my strongest lifelong special interest, Doctor Who. I was working on my thesis in the Studio for about a year before it had even been formally proposed, which proved to be invaluable research. Though I had feared the same things as I do with all of my projects—that it was too silly, too pedestrian, too immature for academic study—I found that I had perhaps the opposite problem. I knew far more about my topic than any professor who might serve on my committee, which turned out to be not much of a problem at all. I developed robust self-directed research skills, and my committee helped me where it mattered: in making sure I knew where my blind spots were and had the skills to see the shape of what I did not know. I was, as many mentors and peers informed me and I would not come to believe until very recently, doing Master’s level research in my undergraduate degree, entirely of my own accord.

I wasn’t alone in this. My classmates and close friends were actively advancing their fields. In January, the week before our spring semester began, we were invited back to campus early to work on our theses in a more community-centered setting. Five of us attended (a full 25% of the class) and participated in structured activities to help hone our research and writing, but the real magic of the week happened in the evenings when we were still spending time together, and, miraculously, still talking about our theses and enjoying it immensely. Though we were spread across unrelated disciplines, we talked through creative and logistical problems in our work alongside playing party games and having movie nights. I learned so much from my fellow seniors, and I can only hope they learned from me. This continued throughout the semester—we held each other close, feeling an apocalyptic foreboding about graduation, though we couldn’t know the extent to which our class was an ending. As I drove away from campus in May, I was inconsolable. I didn’t just want my community back. I wanted to keep thinking, keep writing, keep collaborating in the way that so far I’ve found I only can at Simon’s Rock.

The day before graduation, I and three other seniors from different disciplines represented the Simon’s Rock senior theses to the board of overseers, each giving a five-minute overview of our projects. It was then that I understood how incomprehensible what we do is to traditional education structures as I, in partial Doctor Who cosplay, faced down Leon Botstein’s unimpressed expression while explaining how fan studies can be valuable and important research. I can’t help but hubristically wonder if Simon’s Rock’s withering away is, on some small level, my fault; if my presentation was proof that the senior thesis was not a valuable enough prospect to warrant keeping the Simon’s Rock BA program distinct from Bard’s. I can only hope that my presentation was a drop in the bucket for the other camp: my thesis would not have been possible if I had a traditional four-year education within a specific pre-determined discipline.

Simon’s Rock is, and will continue to be for the next six months, the only four-year college in the world that is specifically an early college. It is not, and myself and other students would emphasize this strongly, a high school. I am a high school dropout, and the years I spent between the ages of sixteen and twenty were not a high school experience. I went to a four-year college, and I will continue to refer to it as such. I have heard from current Bard students that the general atmosphere on campus in light of this news is a different horror to the one Simon’s Rock students are experiencing: they are terrified at the prospect of there being teenagers and high schoolers on their campus, as if the two years they have over a Simon’s Rock freshman have granted them any ontological personhood that they did not have before “adulthood.”

It is frustrating how many observers cannot see that this is precisely the point of Simon’s Rock as an institution; unlike many other early college programs, it has never been about “getting a head start,” “advanced ability,” or “academic rigor,” a term I hate with a passion. Simon’s Rock accepts and moves forward with what has always been true about teenagers: they are autonomous, living, breathing people, with passions and ideas and curiosity. Simon’s Rock students are ready for college, not because they are special geniuses, but because they are people who want to be at college.

The advertisement that led me here in the first place was a mail flyer asking me if I was tired of standardized tests, and I was. I wanted to learn, and I wasn’t effectively learning by filling out worksheets at six in the morning five days a week. The best learning of my life happened when Donald McLelland let me turn in my final biology lab paper as a (well-researched) short story from the perspective of a black-capped chickadee, and when Amanda Landi invited students to her house for campfires and board games, and when Dan Nielson told me he “[loves] the way [my] brain works” after I showed him my spreadsheet of Doctor Who episodes. Learning is an untameable beast, and the best educators know how to communicate with it rather than cage it. By becoming further enmeshed with Bard, I fear, along with potentially losing the outstanding educators who make it what it is, that Simon’s Rock will face more of the pitfall that every other education institution inevitably stumbles over: the endless pressure to prove that our method gets “results” that can be proudly reported to donors at a board meeting.

If I sound like an insufferable hippie, it’s because I am, especially about education. I get it from my Simon’s Rock Education, Polity, and Society undergraduate concentration. As I began to pursue a career in academia, I had held it in my mind that I would one day return to Simon’s Rock as an educator, because I wanted to become a part of the educational method and environment that made me who I am. I have far less interest in the internal politics and soulless bureaucracy of a research institution, or even any research career at all. Without Simon’s Rock, without its place, people, and ideas, I fear that the whole world is a less curious place, and I am not sure if its places of “learning” are institutions I want any part in.

absolutely beautiful, rimon. i don’t know if i could have ever articulated as beautifully what simon’s rock means to me. thank you.